The top ten reasons for the banning or burning of books, in autocracies and democracies alike, are most commonly and widely listed as the following:

Sexual Content

Violence or Graphic Content

Profanity

Racial Themes

LGBTQ+ Themes

Religious Reasons

Political or Social Commentary

Drugs and Substance Abuse

"Inappropriate" for Age Group

Offensive to Cultural or Moral Standards

Most of these will be achingly familiar if you grew up in a proto-fascist, constitutionally racist, nominally Christian, self-proclaimed democracy such as apartheid South Africa.

Most of them are becoming just a familiar if you didn’t.

I’ll give you the global overview in due course. But here, for starters, is the current trend for book-banning in the anti-fascist, anti-racist, nominally Christian, nominally liberal and self-proclaimed democracy of the USA:

In 2023, the American Library Association (ALA) documented 4,240 unique book titles targeted for censorship, a 65% increase from the previous two years. This was the highest number of book bans ever recorded by the ALA.

Source: Gemini overview, 22 - 11 - 2024

While there is and always will be a clear moral imperative to protect children from exposure to pernicious, vile and disturbing verbal and visual content, it seems to me that books — in the Wild West of the current media landscape — are the least likely of places in which they are liable to encounter it.

The puzzle is partly unpicked, in the case of the ALA, by Gemini’s addendum:

In 2023, 47% of the books targeted for censorship represented the voices of LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC individuals. Other books targeted include Lord of the Flies, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe. The reasons for the banning of the latter ones remain unclear.

I can almost grasp why Baptists, Mormons and other Christian nutjobs get so enraged by anything and everything that could encourage their macho Republican sons to become simpering Democrat girls, or vice versa. What I couldn’t understand until my epiphany of a few weeks ago, was how and why Lord of the Flies and To Kill a Mockingbird could possibly be regarded as gateway drugs that threatened to inspire their children to a radical reappraisal of their sexual, social and political identities.

It has subsequently become as clear as daylight. Or as adumbral as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon.

Adults who favour censorship don’t do it to protect their children. They do it to protect themselves.

They are darling buds of May, terrified to distraction by the gentle breezes that presage the approach of life-giving rain.

It’s far more comforting for them to live in the glass conservatories they construct to hot-house their biases, bigotry, chauvinism, intolerance, preconceptions, predispositions, sexism and xenophobia.

And how extraordinary yet predictable it is that the most delicate, sensitive and precious of these fragile blossoms are those same macho monsters responsible for the most atrocious and least forgivable crimes against humanity — when humanity, in their view, excludes all living creatures who breathe the phosphorous poison on the other side of the glass.

They can see their victims, of course. But they can’t or won’t hear their cries or smell their burning flesh or feel their pains of hunger, loss, abandonment or the bleakest and most biblical of all their fears and depairs.

These delicately sensitive whining and whimpering guardians of public morals will expurgate a story about a boy who has innocent fantasies about what it would like to be a girl. Yet they are the very same people who will gloat over the uncensored visions and descriptions of the consequences of their own perversions, degeneracy and debauchery in the horror films they made themselves: the snuff-porn of their fantasies, the darkest grotesqueries and titillations of the torture scenes of their dreams; the images from Palestine; their auteur films of the squirming, bleeding, screaming consequences of their unrestrained evil.

Enough.

It’s illuminating to note, in this dreadful context, that only twenty to thirty percent of books are banned for right-wing political discourse. By far the majority of them are banned for challenging existing power structures, both right and left. This will become increasingly significant as my argument unfolds in the chapters to follow.

Source: Gemini overview, 22.11.2024

The immediate point is this: The list of the ten reasons for censorship, and for book banning in particular, fails to include the most significant and consequential of them all.

The eleventh reason, oddly or deliberately omitted, is by some measure the most shocking, disturbing and terrifying of them all. It’s more shocking, indeed, than all of the others put together — than all of the shocks I could ever have suspected, anticipated or imagined in the darkest depths of the cruellest fantasies I’ve ever had to expunge from the airless and suffocating Cango Caves of my mind.

We’ve all be down there. I told myself at the time that I needed to exercise my negative capabilities. Isn’t that where all writers go to plumb the psychology of their most villainous creations?

Think Mary Shelley, H.P. Lovecraft, H.G. Wells, Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, Neil Gaiman or Chuck Palahniuk. They’ve all descended to the darkest depths of it to find their inspirational gold. So, too, all the great novelists who have ever afforded us a glimpse of life-affirming hope in a world of personal or political despair.

If you can’t describe evil you’ll never be any good at describing good. See my observations re Shakespeare’s Iago, MET passim.

Then you come up to the surface wondering if there’s enough Lysol in all the world to cleanse that much filth from your mind.

This eleventh reason for censorship is deeper, darker and more consequential than any of them. It’s the reason for censorship that has itself been censored; the reason for book banning that has itself been banned.

It’s also the most subtle and most Machiavellian of them all. And unless I have accidentally lapsed into a Nostradamus-like coma of febrile fantasies, paranoid prognostications and even more feverish fears, it’s the form of censorship that has all the while been preparing us for this:

I’m looking at a map. I measuring the distance between Kyiv and Moscow, between Tel Aviv and Baghdad, between London and Cape Town, between Beijing and Brazil, between Washington and insanity. I’m measuring the average circumference of nuclear clouds.

Yes, the missing reason for banning books is as dark as this.

The quote below is a teaser to what follows in the forthcoming chapters. You don’t have to read between the lines. Just read the lines and you will know where I’m heading.

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.

James Baldwin

To be continued before it’s too late.

There was a time, not so long ago, when we assumed that the banning and burning of books was the preserve of the self-espoused dictatorships of the world — of Hitler’s Germany, of Stalin’s Russia, of Mussolini’s Italy, of Mao Zedong’s China, of Pol Pot’s Cambodia, of Idi Amin’s Uganda, of Pinochet’s Chile, of John Vorster’s South Africa and so on and so forth from despair unto oblivion.

So it comes as something of a surprise to discover that book-banning is alive and flourishing in most of the world’s self-espoused democracies all the way from Amsterdam to Zagreb. It’s even more disturbing to know that most of them are novels.

I fully understand the banning of anything and everything that is deliberately mendacious or malicious, and certainly of any public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence toward a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation, as per the definition of hate-speech.

But why the novel? Why pick on made-up stories about made-up people in made-up circumstances in made-up times, places and circumstances? Why pick on fiction?

Why To Kill a Mockingbird? Why The Catcher in the Rye, Beloved, The Kite Runner, Ulysses, Lord of the Flies, The Great Gatsby and even — madly and ironically — Nineteen Eighty-Four itself?

The list goes on and on. It includes many of the most profound and moving novels ever written. Search “most banned novels” on Google to see the full and unutterable craziness of it.

Why, how, where, when and wtf?

The answer came to me slowly and painfully.

Painfully because, as hard as it sometimes is, I try with my teeth and my asshole tightly clenched to see the best in people who are vocally sexist, explicitly racist or Tottenham fans.

My wife would often help to expatiate my suppressed rage by saying, “Maybe they’re very nice to their children.”

Slowly because, in apartheid South Africa when I was barely old enough to understand her words or their implications, I was nurtured by my mother to believe in the moral superiority of the western democracies who, with the help of my father in Italy, the Levant and Egypt, had combined to defeat the fascist ideals of Hitler, Mussolini, Tiso, Horthy, Tiso and Hirohito. And which western democracies, sooner rather than later, would surely intervene to save South Africa from itself.

And even more slowly because the cowboy films we saw at Maclin’s Cafe in Mooi River routinely depicted the bad guys wearing black hats and the good guys wearing white ones.

And slower still because the biggest pay-cheques I ever took home were from advertising agencies in South Africa, Mexico and London, which had served, logically and greedily enough, to put a disproportionate amount of what little faith I had left in humanity in general into an unquestioning belief in the moral superiority of liberalism, neoliberalism, the perfection of the market, and the self-evident humanitarianism of the democratic ideal.

Indeed, a word liberally employed in the 19th century novel, the pay-cheques were sizeable enough to erase from my once-troubled conscience the vague memory I had of doubting the moral legitimacy of the Vietnam War way back in the early seventies when my adolescent hopes for a kinder and fairer world had foolishly inspired me to question the moral legitimacy of that tragically pointless conflict.

Well, come on all of you, big strong men

Uncle Sam needs your help again

Yeah, he's got himself in a terrible jam

Way down yonder in Vietnam

So put down your books and pick up a gun

Gonna have a whole lotta fun

Yeah, come on Wall Street, don't be slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go

There's plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade

Just hope and pray that if they drop the bomb

They drop it on the Viet Cong

Yeah, come on Wall Street, don't be slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go

There's plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade

Just hope and pray that if they drop the bomb

They drop it on the Viet Cong

And it's one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don't ask me, I don't give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam

And it's five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well, there ain't no time to wonder why

Whoopee! We're all gonna die

Well, come on generals, let's move fast

Your big chance has come at last

Now you can go out, and get those Reds

'Cause the only good Commie is the one that's dead

And you know that peace can only be won

When we've blown 'em all to kingdom comeAnd it's one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don't ask me, I don't give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam

And it's five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well, there ain't no time to wonder why

Whoopee! We're all gonna die

Well, come on generals, let's move fast

Your big chance has come at last

Now you can go out, and get those Reds

'Cause the only good Commie is the one that's dead

And you know that peace can only be won

When we've blown 'em all to kingdom comeEvery so often, on the long and winding road that was supposed to lead me towards adulthood, a shadow of incongruity would briefly occlude to question my direction of travel.

One of them was as sombre as this:

Yes, the BDS movement of the west eventually persuaded the apartheid government to release Mandela. But the wars we had been fighting on the ground in Angola, Mozambique with Western-supplied missiles and landmines were seminally against a small army of Cubans, the proxies of the baby-eating communists of China and Russia.

No amount of hand-washing could soothe or erase the cognitive dissonance of this blunt and bloody fact. Our ostensible enemies, the ones we were fighting to preserve the notional democracy of apartheid South Africa, were putting their lives on the line to liberate Angola and Mozambique from Portuguese colonial hegemony. So that they could become, well, democracies.

It’s the kind of information that gives you pause.

Or, as Freud noted so brilliantly, “Where does a thought go when it's forgotten?”

The answer is that it hangs around in the body searching for a window to look out of.

While the Cubans were being massacred in droves by our US and UK-supplied hardware and deathware, and friends of mine were losing their limbs and their lives to preserve the sanctity of the South African apartheid state, the western world was counting the cost of a 0.5 percent loss of the operating profit on their sales of skin-whitening creams.

As it were.

Cuban military engagement in Angola ended in 1991, while the Angolan Civil War continued until 2002. Cuban casualties in Angola totaled approximately 10,000 dead, wounded, or missing.

Wikipedia

Greefswald had shredded the last of my lingering hopes for the intervention of a deity who gave even the most casual of fucks about the injustices of the world in general and my world in particular. It turned out to be a blessing very poorly disguised.

Remove faith, fate and all the attendant superstitions that cling to them like ants around a stray breadcrumb on the kitchen floor, and you’re left with the astonishing and terrifying revelation that the human race is in charge of its own destiny. Just as I very slowly recognised I was in mine.

Perhaps, or almost certainly on reflection, in a desperate attempt to avoid the responsibility of having to chart my own course through the choppy seas of adolescence, adulthood, fatherhood and hoodlessness, I turned to the novel for solace.

I read passionately, indiscriminately and voraciously. As desperately stupid and unfair as the banning of television seemed at the time, it helped considerably that I was in my early twenties before the apartheid government reluctantly agreed to allow us our first glimpse of the idiot box.

“I find television very educating. Every time somebody turns on the set, I go into the other room and read a book.”

Groucho Marx

. in I continued to cling to my faith The pain was because it obliged me several years ago to begin to reexamine my blind faith ,

All of those illusions would soon die unspeakably terrifying deaths in Beit Lahiya, Deir al-Balah, Gaza City, Jabalia, Khan Yunis and Rafah.

But the question remained. What kind of crazy connection could there be between the genocide in Palestine and the banning of, say, “The Bluest Eye,” by Toni Morrison in Dallas, Texas?

The answer arrived, not as a single, blinding revelation, but in barely digestible chunks.

The first chunk went like this:

It’s a perverse but indisputable fact that liberals and liberal democracies are more terrified of socialism than they are of fascism. It’s also entirely logical and eminently explicable:

It’s the money, honey.

The accumulation of wealth is synonymous with the accumulation of power — philosophically, practically and politically. Socialism is a threat to the rich and therefore to the powerful. Fascism isn’t.

This fear holds as true for liberally-minded individuals who espouse the principles of liberté, égalité, fraternité as it does for corporations who model their internal management structures on the five principles of fascist organisations, viz, authoritarianism, nationalism (where the corporation is the nation), hierarchy, elitism and militarism (where marketing is the military).

And since most of the world is run by corporates rather than by individuals or political parties, and since 132,989,428 American adults work for corporates, which is to say very nearly forty percent of the US adult population, it stands to reason that a very large constituency of the western world’s adult population would have weaned themselves off their mothers’ milk of human kindness to replace it, sooner or later, with the corporate Kool-Aid of kill or be killed.

The second chunk was a reflection on advertising, or propaganda as they call it here in Brazil. It went like this:

I have written about this elsewhere, not in the vain hope of making anyone see reason, but simply to propitiate a conscience troubled by thirty-odd years of complicity in selling unnecessary goods and services to people who mostly couldn’t afford them.

These include the noxious ideas I peddled on behalf of the apartheid government in my three-year stint as a journalist for the South African Broadcasting Corporation in the early 1970s where I mastered the ten types of lies and deception, viz: error, omission, denial, falsification, misinterpretation, bold-faced lies, white lies, exaggeration, pathological lying and minimization.

In those days, twenty or so years before some busy-body on the internet could point an accusing finger at the vast abyss that separated what the apartheid government was saying from what the apartheid government was doing, we learned soon enough that we could safely dispense with the subtleties of error, omission, denial, misinterpretation, white lies, exaggeration and minimization developed and recommended by our colonial masters at the BBC.

Blatant, bold-faced, pathological lying alone would do the trick. And it would go unchallenged in every case.

Times have changed, of course. And so have the ways in which we receive and disseminate information. In the space of four or five decades we have advanced epistemically from rubbing sticks together to make small fires of disinformation, to the current equivalent of nuclear war between fact and fiction. In all that intervening time I assumed the ten types of lies and deception had remained more or less constant.

I was disabused of this naive assumption only a couple of days ago when I stumbled a day or two ago across a single shocking sentence that struck me as containing all of the ten types of lies and deception rolled brilliantly into one. It seemed impossible. I read it again and again. But, yes, there it was, a masterpiece of mendacity, a glittering jewel in the crown of obloquy — the veritable Koh-i-Noor of calumny.

And just when I thought the BBC had nothing left to teach me about propaganda. I will get to that in due course.

When neither my mad musings on the fascist instinct, nor this angry aside on the epistemic shitstorm that seems as unstoppable as the upwards-ratcheting numbers of flood disasters currently overwhelming the world at every point of the compass, could help to explain the banning of so many of the most admired novels in the world, I was obliged to look elsewhere.

Elsewhere turned out to be under my nose. All I had to do was ask the right questions.

Would the world be a better place if people read more books?

Of course, asserting that reading can fix the world's problems would be naive at best. But it could help make it a more empathetic place. And a growing body of research has found that people who read fiction tend to better understand and share in the feelings of others — even those who are different from themselves.

https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/how-reading-fiction-increases-empathy-and-encourages-understanding

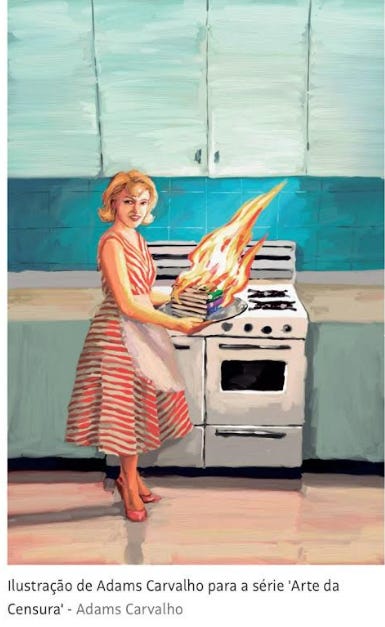

I have the Folha de S.Paulo to thank for pointing me in the direction of the answer, specifically their article of a few days ago detailing the routine removal of “controversial” books from American public libraries brilliantly illustrated by Adams Carvalho’s image (above) and captioned “This is America”.

Which took me to the history of book burning, which took me in turn to the banning of novels in particular, and which got me wondering why fiction appeared to be a bigger threat to both despotic and democratic governments even than the unadorned facts that disclose their daily failings in the free or not so free press, as the case may be.

The answer, it turns out, is stunningly, shockingly and blindly obvious:

Studies suggest that people who frequently read fiction texts become more empathic because fiction simulates social experiences, which is an opportunity for people to practise and improve interpersonal skills.

McCreary & Marchant, 2017; Mumper & Gerrig, 2017

Search and ye shall find another hundred studies confirming the same thing.

The Harvard Business Review, not exactly famous for celebrating the touchy-feely stuff of, say, Wuthering Heights, gives us this:

Research suggests that reading literary fiction is an effective way to enhance the brain’s ability to keep an open mind while processing information, a necessary skill for effective decision-making. In a 2013 study, researchers examined something called the need for cognitive closure, or the desire to “reach a quick conclusion in decision-making and an aversion to ambiguity and confusion.” Individuals with a strong need for cognitive closure rely heavily on “early information cues,” meaning they struggle to change their minds as new information becomes available. They also produce fewer individual hypotheses about alternative explanations, which makes them more confident in their own initial (and potentially flawed) beliefs.

https://hbr.org/2020/03/the-case-for-reading-fiction

Case after case concludes with the same insight. Reading fiction puts you in the shoes of the heartbroken and the heartless, of the migrant and the miser, of the kind and the careless, of the hopeful and the hopeless, of the brutalised and the brute. Novels teach us to think with our feelings, to explore with our imaginations, to see the world through the eyes, ears, thoughts and dreams of people very different from ourselves.

People who read fiction have been proven, definitively, to be more empathetic than those who don’t.

James Baldwin’s observation, quoted above, is telling. As is this:

“A great book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.”

William Styron

State censors ban books for precisely this reason. They don’t want you to live the lives of others. They don’t want the unwashed masses to feel, think or explore. They don’t want them to empathise with unknown others. Palestinian children spring to mind.

More specifically, they don’t want them to doubt, question or challenge the official narrative that keeps them fearing change, submitting without question, and swallowing their lies — hook, line and sinker.

Empathising with “the other” is the gateway to subverting the status quo.

They must always be they. They must never be us.

The map below, showing the history and frequency of book-banning by country, tells a thousand stories:

I can testify personally to the painful truth of being dumbed and numbed by lack of access to the most interesting and provocative 20th century literature.

During the apartheid era I grew up in, the only books that weren’t banned were the ones the censors didn’t understand. Hence my youthful diet of terrible 19th century romances. It’s hard to say whether I learned such empathy as I like to think I have from Jane Eyre or from eating putu in smoky mud huts.

While Enid Blyton’s truly dreadful stories were quite rightly banned in many countries because her Golliwogs ridiculed Black men, the same stories were banned in South Africa because Noddy had a black person as a friend.

That was the tip of a large iceberg. While other countries were banning explicitly racist books, South Africa was banning books that weren’t racist enough. The same was true of all novels that weren’t fascist enough, that didn’t depict communists as monstrous baby-eaters, or that failed to underline the cultural superiority of white people in every aspect of human endeavour. Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da was banned for its last, homo-provocative verse:

Happy ever after in the marketplace

Molly lets the children lend a hand

Desmond stays at home and does his pretty face

And in the evening she's a singer with the band, yeah

The subject deserves a book, not a blog. Suffice it must to say South Africa’s apartheid censors were as draconian as they were stupid, and we can move quickly on.

It was the Nazis who made book-burning famous, of course. I’ve been to the memorial of it, the chilling “Empty Library” by Israeli sculptor Micha Ullman set into the cobblestones of the Bebelplatz in the centre of Berlin.

It’s cold, terrifying and industrial.

I now understand that their motive wasn’t to destroy knowledge. It was done to kill the remotest possibility of empathy in Hitler’s opponents.

Look at book banning in any country, at any time, and the motive will be the same. It’s done to kill empathy for otherness of any kind — of nationality, of race, of sexuality, of political sensibility; of a different moral stance on right or wrong.

Note that democracies are as guilty of it as autocracies. Race, language, culture and history make not an iota of difference. The book-banners do it to protect their interests. And those interests are always in protecting the status quo of the religions, the politics, the cultures, the world-views and the spiderwebs of command and control that have facilitated the accumulation of personal wealth, the comfort, and the authority of the beneficiaries.

At the very heart of it, the shared enemy of these despots of every materialist stripe and every political colour is always the same thing:

Empathy.

Which brings me back to the empathy-killing strategy I had forgotten to include in my list of ten effective lies and deceptions.

The rewriting of history is so common I had taken it for granted. Every country has done it, and every country continues to do it. It’s a topic so vast and complicated in each and every case there is hardly any point raking through the cold ashes of it.

Someone says, but who got here first!?

And it goes nowhere from there.

What I hadn’t considered until this week was that history includes what happened yesterday and the day before yesterday. I had always thought of history as, well, historical.

In every country in the world, revisionists will be hard at work rewriting and reshaping the way their history should be read and understood. Whitewashing will undoubtedly outnumber confessions of guilt by several million gallons of the stuff. It’s what they do, or what they’re paid to do. But it’s usually more dusty than dirty.

What I hadn’t conceived of - in a world in which everyone can know everything at once - is the breathtaking revisionism of events we witnessed with our own eyes on television just a few days before yesterday.

Then this particular case obliged me to to add the following new and revelatory empathy-management strategy to my list: comfort the perpetrators by blaming the victims.

It turns out that the considerable, damning and disgusting evidence forensically documenting what actually happened in Amsterdam on the night of November 7th must have hurt the feelings of the perpetrators. They clearly weren’t getting enough empathy.

Enter Auntie Beeb to comfort them:

A fragile calm hangs over the Dutch capital, still reeling from the unrest that erupted a week ago when Israeli football fans came under attack in the centre of Amsterdam.

BBC website, 15th November, 2024

Jeezuz, okes. Did someone say a bad word or call you by a bad name?

Shame, man.

Try reading a book, Ffs.

Maybe Judas, by Amos Oz.

Author Headshot

By German Lopez

Good morning. Today, we’re covering the escalating war in Ukraine — as well as Trump’s appointments, Gaza’s wounded and Rafael Nadal’s retirement.

But I’m heading to a question much bigger than who are the goods guys and who are the bad guys.

At times I felt you had some how got into my mind, my memories, and my visions of the world I remember. Wonderful to hear some of what I thought to be, my secret and private thoughts, guilt and confusion; brought to life with your mastery of words. And then, to be given answers that I have been unable to find,, I realise we/I are indebted to those of you who dig through the archives, craft your sentences so that the words carry the weight needed to land like a good left hook. Good deep stuff, bra!